Silence and Speech in “Lecture on Nothing” and “Phonophonie”

| September 9, 2017 | Posted by Webmaster under Volume 24, Number 3, May 2014 |

|

Zeynep Bulut (bio)

Abstract

There is no absolute silence, just as there is no absolute loss of hearing or voice. We tend to understand the limits of silence and speech as correlated with our physiological and discursive thresholds of hearing and voice. Yet there is more to hearing and voice, more to be added to the discussion of silence and speech. In the past 25 years, historical and theoretical studies of sound and voice have helped us to reconfigure what constitutes the thresholds of hearing and voice in the first place, and to imagine what’s more and/or what could be otherwise. Writings on opera, film, experimental music, radio, and performance art, voice and speech production, and hearing and speech disabilities have scripted the voice as a strain – a zone of sounding – between the materiality of the body and the immateriality of language.[1] Problematizing this tension, other essays on voice contest the physical, phenomenal, imaginary, and political limits of the voice.[2] In line with this trajectory, I discuss the ways that experimental music and deaf performance can critique the presumed limits of hearing and silence, and the ways they can suggest new limits of voice and speech while enacting a performative language. I look at two examples: Phonophonie by Mauricio Kagel, and Lecture on Nothing by John Cage.

Written in four columns and divided into five rhythmical sections, Cage’s famous text Lecture on Nothing punctuates the actual moments, unfolding spaces, emerging sounds, and latent ideas of silence within everyday speech. Berlin-based artist and scholar Brandon LaBelle’s rendition of Lecture on Nothing features an audio recording of the text read by a deaf person, David Kurs. Kurs’s reading encourages us to question what it means to speak without hearing one’s own voice out loud. The idea is neither to stigmatize or pathologize deafness nor to normalize or suggest a metaphor of the performative voice through deafness.[3] The suggestion is that by listening to a deaf person’s voice, one will reconsider the normative thresholds of the hearing body and the capacities of the speaking voice.

To what extent can one hear one’s voice in the act of speech? What is being said in this process? Who is entitled to say it and in what way? And after all, what is heard? LaBelle’s interpretation of Lecture on Nothing poses these questions while also asking us to look at the performance of what is silenced. As Tobin Siebers posits in Disability Theory, “disability creates theories of embodiment more complex than the ideology of ability allows” (9). What Siebers suggests here is important for my point. I am interested in Kurs’s reading as a way to consider the embodiment of sound and voice in the act of forming speech. In other words, I would like to draw attention to the creative potential of Kurs’s voice and speech as it is, without adjusting or restoring it to a normalized form of vocal expression. With its tempo, rhythm, and articulation, Kurs’s speech unsettles what we consider regular or normal speech. One can argue that Cage already forces such creative moments into formalized musical units in Lecture on Nothing. Nevertheless, I would argue that these formalized units should also be considered an aesthetic – a relational – intervention, which would allow us to expand both on the conceptual and on the operational limits of silence and speech.

In his book Concerto for the Left Hand, Michael Davidson asks: “How might the aesthetic itself be a frame for engaging disability at levels beyond the mimetic? How might the introduction of the disabled body into aesthetic discourse complicate the latter’s criteria of disinterestedness and artisanal closure?” (2). Davidson’s questions understand aesthetics as a realm in which one can contest the discursive representations of the disabled body, and propose that the disabled body’s induction into an aesthetic discourse may critically intervene in the aesthetic discourse itself. These propositions are useful for situating the premises of LaBelle’s rendition of Lecture on Nothing and Kurs’s performance in the fields of experimental music and disability studies. I argue that LaBelle’s rendition and Kurs’s performance crystallize Cage’s use of silence not only as a musical and conceptual idea, but also as a site in which we can reflect on what constitutes silence physically, culturally, and politically. The introduction of Kurs’s deafness and voice into Lecture on Nothing effectively encourages us to open up Cage’s aesthetic conception and musical formulation on silence, to undo our preconceptions about the physiologically and culturally habituated limits and limitations of the hearing body and speaking voice, and to hear the syncope between acts of hearing and speaking. In doing so, one can expand on given forms of speech and narratives of silence, find the performative potentials of speech and silence, and be attuned to the resonances between discursively different voices.

Phonophonie, Kagel’s melodrama for voice, percussion, and tape, directly contributes to this discussion. The piece integrates seemingly marginalized characters—a singer, a ventriloquist, a mimic, and a deaf-mute—in one performer by means of vocalization. The singer performs extreme sound with extended vocality and inclusive drama; the ventriloquist supports this extreme sound by falsifying the direction of his voice in such a way that the audience cannot decide where the voice comes from; the mimic reinforces the illusion that the ventriloquist creates with his voice by using his whole body; and following the mimic, the deaf-mute speaks with his body, imagining the existence of an extreme silence. Situating the extreme sound and the extreme silence side by side, the sonic similarities between the voices urge us to question the discursive attributes we assign the deaf-mute character. Kagel employs the human voice as a shared sense, a site of co-sounding, an ordinary yet specific embodiment. This use of the voice feeds into Kagel’s “instrumental theatre,” a term associated with Kagel and explained by musicologist Björn Heile that makes it possible to understand the aesthetics behind Phonophonie and its resonance with Lecture on Nothing.

Kagel was trained in Cologne as a part of the European avant-garde school that deals with serial music composition, yet he was also preoccupied with the French electroacoustic tradition that amplifies concrete sounds, and he was aware of the American experimentalism that foregrounds everyday sounds and actions as the main medium of performance. In The Music of Mauricio Kagel, Heile posits that this fruitful mixture encouraged Kagel to create a new genre, “instrumental theatre.” Heile defines the term as the “dramatization of musical performance” and the “musicalization of experimental theatre” (35). Like John Cage, Henry Cowell, Dick Higgins, and La Monte Young, Kagel suggests music can be theatre. Neither music nor theatre accompanies the other: “music does not accompany action, but it is action,” writes Heile regarding Kagel’s use of theatre and music (35-40). Instead of leading to pre-imposed sounds as imagined by an author or director, physical action leads to the sound itself created by a performer. Instrumental theatre thus articulates the physicality of music, sound, and performance.

For Kagel, the human voice is one of the most effective engines for exploring such physicality. Before and beyond words, Kagel emphasizes the gestural marks, silences, interruptions, spatial emergence, spread, physical acts, and extensions of the voice. The everyday voice seems to operate like glue in this aesthetic. It brings various actions and sounds together and triggers the imagination of everyday scenes. By means of the voice, Kagel deals with the constantly changing and contested nature of the self and its multidimensional and polyphonic texture in human interaction. Heile summarizes this idea as follows:

Kagel’s work makes the idea of authorship as direct expression of a unified, self-identical ego an impossibility. If, on the other hand, one allows for inherently plural, inclusive, fluid and perhaps even contradictory subjectivities then Kagel’s works appear as emphatically human documents. (3)

Heile’s reading effectively describes the core of Phonophonie: a single performer voicing four different personas. Though they are historically disconnected, these four personas sound similar. Partial and reciprocal, they speak a common alphabet. Like Lecture on Nothing, Phonophonie urges considering deafness not as a case that requires social distance or medical rehabilitation but as a case that provides a performative language, a language that marks the resonance between a variety of speaking, singing, sensing, and signing bodies.

On Deafness: A Possible Voice

One of the principal texts on histories of deafness, Carol Padden and Tom Humphries’s Inside Deaf Culture spotlights the discourse of deafness in the United States since the nineteenth century and calls attention to the lack of any unified “deaf culture.” There are different histories of segregation, stories of conflict, and impositions of silence instead. As Padden and Humphries recount, before the nineteenth century, “disabled” children—“deaf, blind, poor or otherwise”—were not institutionally segregated (18-19). They were home schooled and supported by their immediate families and neighbors. With the rapid growth of the cities of New York, Hartford, and Philadelphia, however, the idea of social distance between the “disabled” and the “normal” became dominant as “a uniquely nineteenth-century phenomenon,” according to Padden and Humphries (18-19). The larger construction of normalcy, and of the so-called idealized body and of disability, as Lennard J. Davis explains in his introduction to The Disability Studies Reader, derives from the standardization – and thus marginalization – of human traits and capabilities based on the foundations of eugenics and fingerprinting in the nineteenth century (3). The science of eugenics generated the conditions for defining and excluding “defectives, a category which included the ‘feebleminded,’ the deaf, the blind, the physically defective, and so on” (Davis 3-4). Davis writes that Francis Galton’s notion of eugenics coincides with Alexander Graham Bell’s speech, “Memoir upon the Formation of a Deaf Variety of the Human Race,” which underlines the “‘tendency among deaf-mutes to select deaf-mutes as their partners in marriage with the dire consequence that a race of deaf people might be created” (4). These accounts convey the way in which nineteenth-century discourses of normalcy—and of disability—directly qualify deafness as an essential category that needs to be controlled and managed, if not always through hospitals.

In this context, the perceived need for social distance led to the invention of separate institutions, where deaf children could be “educated” and “rehabilitated” (Padden and Humphries 29). Even though education allowed deaf children to acquire new tools of expression such as sign language, it also treated them as “inmates and objects of study” (29). Thus, deaf students’ education was not simply a regulation but also a medical examination. This analysis shows us (1) that verbal language can block other forms of communication, and thus shadow the possibilities of being present otherwise, and (2) that its lack can usually be translated into a lack of voice and body. The analysis also shows that training can generate negative power as well as positive power. As Padden and Humphries also say, given that “the watched and the observed cannot speak for themselves,” an abuse of power may occur (30-31). Using Foucault, they include among the strategies of power “silence, perpetual judgment that is a constant call about the inmates’ conditions, and recognition by the mirror that is seeing one another and then assuring similar conditions” (32). Padden and Humphries interpret the last strategy, recognition, as a positive force that avoids the situation of the “inmate,” as “recognition of the self as possibles” (33).

I would add that “recognition of the self as possibles” creates the urge to find and express one’s voice. Deaf people have a voice, even though they do not always identifiably know it. The human body always responds to vibrations, even to the ones below and above the hearing threshold. Deaf people can hear their own voices in their bodies. But as history shows, the pursuit of the voice is neither direct nor smooth. The issue is the way that deaf people use their voices. The human voice is an object, “an object for Deaf people to manage,” as Padden and Humphries argue (100-1). The idea of “managing voice” illuminates the limits of spoken language. Deaf people are encouraged not always literally to speak, but to “borrow the others’ voices” (100-1). In other words, they speak through others’ voices. Padden and Humphries suggest that we should then consider voice for deaf people not simply as a biological or communicative medium, but also as a technology that requires being “managed and cultivated” (100-1).

In line with this notion of the voice, one can also consider the tension between sign language and spoken language in deaf education. Jonathan Rée’s book, I See Voices: Deafness, Language and the Senses, focuses on the tension between the system of visible speech and oral communication. In regard to both signed and spoken language, we still need to ask the following questions: What constitutes a speaking voice, and what makes a voice speak? These questions manifest fruitfully in deaf theatre. Deaf theatre combines forms of sign language and spoken language, possibly because it needs to communicate deaf theatre to larger audiences and to integrate deaf actors with other actors. It is of course true that this integration makes deaf people more visible in the public and extends their “management” of the voice to performance. But at the same time, the blend of signing and speaking expands the understanding of voice and speech for deaf actors’ collaborators and audiences.

In his well-known article “The Scandal of Speech in Deaf Performance,” Michael Davidson exemplifies the combination of sign and spoken language by a collaborative project by deaf poet Peter Cook and hearing author Kenny Lerner, I am ordered now to talk. Cook speaks. Lerner signs. Davidson refers to a description of the project by another English and disability studies scholar, Brenda Brueggemann: “Cook’s voice is loud, monotone, wooden, ‘unnatural,’ nearly unintelligible,” while Lerner’s signs are “a bit stiff and exaggerated as well” (218-19). Davidson highlights the way that we perceive deaf voice and speech as “scandalous.” Nonetheless, he associates the scandalous with the “performative,” and draws attention to the way that deaf performance establishes not the lack but the presence of the voice. By performative, Davidson means “a form of speech that enacts or performs rather than describes” (216). In the volume Bodies in Commotion: Disability and Performance, Carrie Sandhal and Philip Auslander continue this line of thought, while emphasizing that disability is “a performance of everyday life” (1). Sandhal and Auslander thus encourage us to think of deafness as being “out of the ordinary” in a way that asks for “a pause and consideration” of the very ordinary itself (2). Such a pause is key to the performative.

Cook’s vocalization and Lerner’s signing together present a performative narrative that can be understood to challenge the habitual understanding of speech and assumptions about who is entitled to speak in what way. It is exactly in this context that I would like to discuss Lecture on Nothing and Phonophonie.

On Lecture on Nothing: A Possible Silence

Lecture on Nothing first appeared in Cage’s famous book Silence. For Cage, silence is sound, or more precisely, a zone of sounding with other sounds. Silence is an opportunity to be aware of one’s very present, one’s own body and external world. It is a marker, a negative and interruptive moment, where one stops and thinks, that is, where one stops thinking and allows oneself to be affected by the world. Silence, Cage suggests, is a medium for hearing and being heard by another. It cannot be expected, presumed, scripted, or idealized. It cannot be pure or absolute either. The rest of silence emerges with a kind of restlessness, of nausea produced by a lot of sounds.

In Lecture on Nothing, Cage musically formalizes this tension in the use of silence. He punctuates the appearances of silences in a rhythmic form. In doing so, he articulates silences as plural, in which one can hear all possible sounds in their contingencies as amplified and intensified. LaBelle’s rendition of Lecture on Nothing appropriates this philosophy. The rendition “aims to further explore silence as a complex signifier by giving us a voice that cannot hear itself” (LaBelle). LaBelle’s choice helps us ask what makes a speaking voice sensible, and how such sensible voice can expand our understanding of silence. Indeed, this theme seems to be explored from Cage’s very first recitation of the piece in the ‘50s, in which he explores both the musical and the sonic limits of speech, as well as of silence. Since then many others have performed the piece.

The most recent version is by stage director Robert Wilson. It is perhaps worthwhile to mention Wilson’s interpretation here. In collaboration with composer Arno Kraehahn and visual artist Tomek Jeziorski, Wilson transforms Lecture on Nothing into a theatrical production. The stage is covered with newspapers. Dressed and painted in white, Wilson sits at a table motionless. Banners with fragments of Cage’s text cover the background. Occasionally visuals are projected. Loud electronic sounds are played together with periods of silence and Wilson’s own reading. More strikingly, Wilson plays the recording of Cage’s voice while sleeping on stage. In one of his most recent interviews, when asked about his conversations with Cage, Wilson refers to Gertrude Stein and his difficulty in understanding Stein’s writing (Riefe). Cage suggested to Wilson that he should listen to recordings of Stein’s speaking voice. As Wilson recounts, listening to Stein’s voice helped him make sense of her writing. This realization seems to contribute to Wilson’s keen interest in the physicality of language, in the loss of a given grammar and narrative, in the embodied movement and distribution of words, and in the visceral imagination and much less translatable affects of sounds.

Lecture on Nothing is not terribly open to interpretation. There is a particular rhythmic structure that needs to be followed by the performer. But there is also an event of reading that requires the rise and fall of a speaking voice. I refer to Wilson’s interpretation so as to draw further attention to LaBelle’s choice and Kurs’s reading. In Kurs’s reading, what we are exposed to is again—and even more tangibly—the physicality of language and its power to unsettle the given limits of who is entitled to speak in what way. As shown in the text, there are rhythmically divided pauses and punctuations between the words (see the Lecture). Kurs’s voice sounds flat, yet is also marked with his rhythmic reading. Despite the rhythmic and structural divisions of the text, Kurs’s reading moves without flowing or growing. Some of his words are intelligible; some others are not. Between the words, his breathing and mouth noises are audible. I cannot tell to what extent Kurs heard himself or how his words appeared to him. I can only imagine these things. The physical act of utterance can heighten one’s feeling of bodily presence and the movement of mental images. The physical act and context of speech are obviously related to what is said or uttered. Yet, drawing further attention to the act of uttering articulates one’s body as a marker of time and space, and articulates what is uttered—be it words or word-like sounds—both as an interruptive moment pointing out the space and as a catalyst for the bodily flow extending the space. The attunement to physical action then, before and beyond the given meaning of a word, makes us aware of the distance between hearing and speaking.

We can recall Derrida’s notion of auto-affection here (Speech and Phenomena). Derrida uses this concept to mean hearing-oneself-speak, which he argues is self-proximity. Despite the proximity, there is also a distance—a pause—between hearing and speaking. The lack of immediate relation between hearing and speaking is syncopation, an offbeat moment, what Derrida calls spacing, which also generates a delay between experience and affect. Our voices or the words we say do not fully leave us when we project them out to reach another. I suggest that we consider silence as a syncopated form of hearing-oneself-speak, as an intensified moment of vibration.

Such vibration is perhaps more material for a deaf person like Kurs. Kurs does not hear himself speak in the same way a hearing person does. But given that there is no perfect hearing loss or absolute silence, given that there are degrees of deafness, of distinguishing, identifying, and naming sounds, one cannot conclude that Kurs does not hear himself while speaking. Vibration does matter. Michele Friedner and Stefan Helmreich’s article “Sound Studies Meets Deaf Studies” shows that vibration can provide the common ground for deaf studies and sound studies, while also challenging the limitation of “phonocentric” and/or “eye-centered” discourses and practices in analyzing forms of hearing and speech.

Bearing vibration in mind, let us remember what is said in the text: “I am here…and there is nothing to say…. If among you are those who wish to get somewhere…let them leave at any moment…. What we require is…silence…but what silence requires…is that I go on talking….” (Cage 109). As the text suggests, silence and speech are similarly situated and amplify each other. Silence and speech do not emerge in opposition. Rather, they speak to one another as much as they are spoken. They appear as temporal markers, as spatial gestures. The philosophy behind “nothing to say” or “it is what it is,” and the critique of “prescribing somewhere in advance,” make us consider temporal moments of silence and spatial gestures of speech side by side in the foreground. The text then appears more literal and horizontal.

What is the work of the text, the form of the text here? Cage does not prescribe a given text. He does not necessarily lead us to structural games for creating meaning or causalities. On the contrary, with the prescribed rhythm, with the possible failures and interruptive moments of the speaking voice, he makes us question the grammar of words, the way they are ordered, juxtaposed, coupled, and even enunciated in a given context. Thus the literality here is not about the cultural habituation or immediate recollection/signification of the word, but the physical texture of the text before and beyond such recollections. Consider what is said to be the very surface of what is meant. In this context, neither silence nor speech would be necessarily heard with a regime. In her article “Critique of Silence,” Eugenia Brikema explains the regime of silence, while relating it to various critical discourses:

The regime of silence provides that silence is great because its affirmative form is these terrible privations (every nothingness) and it is great because of its certain failure: its nonappearance is precisely what preserves its ideality…. There is a profound collusion among claims that there is no silence in order to affirmatively capture aural detritus, frame its failed positivity (Cage); the claim that silence itself speaks, that it constitutes the unthought or ground of any discourse (Derrida); and even, yes, the claim that silences are epistemologically possible because of constraints on discursive utterances (Foucault)…. (214, 215, 221)

Brikema posits that all these regimes of silence result in an “ethical impossibility,” in a form of “violence” towards the “being of beings” (214, 215, 221). My position does not affirm any of these propositions. I do not intend to discuss silence as an impossibility of any kind. Quite the contrary, inspired by Lecture on Nothing, I argue for the ontological possibilities of silence, its co-emergence with speech. Kurs’s reading reinforces this side-by-side state of silence and speech in two registers.

First, both the content and the form of the text, as delivered by Kurs, draw attention to a particular performance of deafness, one that both pauses and shakes the grounds of the “deaf moment,” which is presumed to be an incapacity to pursue “the text’s sonic presence, silence, duration in time, breath, voice and ideologically ratified forms of conversation,” as Lennard J. Davis puts it in his book Enforcing Normalcy (107). Second, Kurs’s voice performs a particular voice, one that “resists closure” (see Auslander 163-175). Regarding this second register, I turn to Philip Auslander’s text, “Performance as Therapy: Spalding Gray’s Autopathographic Monologues.” In this text, Auslander discusses the way that Gray narrates different versions of his physical condition; nevertheless, despite the “happy endings” of the stories, Gray’s performances do not resolve into a “closure” or a “cure” (164).

Each performance scripts the physical condition itself as performance.[4] I do not consider Kurs’s reading of Lecture on Nothing as an autopathographic monologue. Nevertheless, I do wish to take a cue from Auslander’s account of performance. Drawing on Gray’s self-narrations, Auslander reiterates the condition of performance, its “economy of repetition” and thus resistance against closure (164). Auslander’s reading highlights the act, the pause of performance. The act does not attempt to fix, repair, or restore incapacity. The act instead employs and exhausts the incapacity, to the extent that one is encouraged to contemplate what constitutes this incapacity as incapacity, and perhaps more so, to embody it as difference. This pause is significant for hearing Kurs’s oral performance. Kurs’s performance does not attempt to restore a voice that speaks in the way that a hearing body does. Kurs’s voice rather provides and becomes a critical space—a site of co-sounding, if you will—for contesting both the physical and the social boundaries of a hearing body and a speaking voice.

As he speaks, Kurs may perhaps more intensively feel his voice as a sounding body. For Kurs, the moment of vibration, the syncopation between his hearing and speaking is his whole body, not a thing, not an object. The flatness of Kurs’s voice can then be qualified also as a surface, which “affects and is affected by” its external environment, like the surface of the text. “If affect describes the ability of one entity to change another from a distance, then here the mode of affection will be understood as vibrational,” writes Steve Goodman (71). To affect—and to be affected—is an effect of vibrational force. Spinoza’s Ethics informs Goodman’s “ontology of vibrational force” (Goodman 71). Goodman constructs the notion of “affectile,” which is a combination of “affect and projectile,” in light of the “ecology of movements and rest, speed and slowness, and the potential of entities to affect and be affected” as portrayed in the Ethics (71). The very surface of Kurs’s voice and reading—its textural and tactual aspects, speed and rest—shall be considered in such terms of “affect and being affected.” But maybe one has to emphasize the touch, the tactile aspect here, the present tense, more than the projectile, the fantasized extension, the future tense of sound. The movement of Kurs’s voice is tactual and textural. This tactile aspect of the voice already exists and operates in everyday speech, in the ways in which everyday speech is deconstructed, on the one hand, and rehabilitated on the other.

Mara Mills’s thought-provoking article “On Disability and Cybernetics” considers the historical and ideological evolution of early and mid-twentieth-century telecommunication technologies. One of them, the hearing glove, was an AT&T-sponsored project by Norbert Wiener. The hearing glove was used to convert speech sounds into tactile vibrations and to regulate voice for deaf people (Mills 78, 79, 85). The goal of this device was to develop a form of the “voice coder” that had been invented by Homer Dudley, and that enabled “tactile communication” and “materialization of speech” through lip-reading for deaf people (Mills 90). Mills points out that the precedents of the vocoder and the hearing glove were efforts to translate acoustic signals into other tangible or visual forms of speech signs:

In fact, Bell engineers had been interested in tactile communication as early as the 1920s, when Northwestern psychology professor Robert Gault requested their assistance with his research. Gault had designed a range of tactile tools to aid deaf people with lipreading as well as voice control. He conceived of speech as something of a blunt object: “If the human voice can be made to break into them through their skins, well and good.” Tactile speech had been a preoccupation of deaf education since the field was formalized in the eighteenth century…. At first Gault believed that vibration—one component of touch—would allow the skin to access sound waves directly. The ear seemed to have evolved from the tactile sense. (90)

Tactile speech and “skin-hearing”—the purpose of another device based on the vocoder developed by the MIT team in 1948—manifest the embodied presence of the voice in the sensory milieu, the skin (Mills 92, 93). Yet these technologies—especially as they progress to artificial intelligence, as Mills reminds us—also lead to the very abstraction of voice, to its mechanical reproduction (101). The double ends of this monstrous spectrum—compression and decompression of speech—suggest an interesting parallel to the combination of the very visceral and the very abstract, the musical and the conceptual form of silence and speech in Lecture on Nothing.

“But now…there are silences…and the words make…help make the silences…. I have nothing to say…and I am saying it…and that is poetry…as I need it,” says Cage (109). Repeat after him, bearing in mind the rhythmic division of the text. The rhythmic interruption—the moments of stopping, counting, breathing and re-uttering—makes one think about “it.” What is “it” that I am saying? At the heart of this question, one can also be reminded of another question: What is “it” that Kurs is reading? It can be the monster of speech, the compressed appearance of speech as word and its decompressed emergence as sounds and as silences. It can be a joint between the human and the nonhuman. It can be both all and nothing. It can be a voice that voices silence and speech, not at the same time, not at the same place, not as equally distributed, but as similar enactments side by side, in parts, and in difference. It is possible.

On Phonophonie: A Possible Speech

If Lecture on Nothing is on nothing, Phonoponie is on everything. With its extreme vocalizations, exaggerated use of gestures, and disproportionate images, Phonophonie provides a medium through which one makes sense of these elements in themselves and as they relate to one another.

The performer who vocalizes the four seemingly marginalized characters is on stage singing live. His face, body, and physical gestures are projected on a screen. His voice is occasionally accompanied or interrupted by prerecorded percussive sounds, which are generated by noisemakers—such as old scratched gramophone records and water gongs, the performer’s prerecorded voice, and a small choir of female voices—that are played back with four speakers. Here I refer to bass singer and composer Nicholas Isherwood’s performance. Isherwood interprets the piece in light of his conversations with Kagel. He collaborated with Kagel on the stage design and suggested using video to project images (i.e., facial gestures). The original score instructs the performer to use a mirror.

The setting of Phonophonie and Isherwood’s interpretation of it inspire a particular acoustic imagination. We are forced to ask where these sounds come from and what the bodies of these sounds look like. We are encouraged to imagine the materiality of sound through the materiality of imagination itself. As such, sound becomes a spatial embodiment for us. This embodiment is the kernel of the voices in Phonophonie. Partial, incomplete, and gestural, the voices of Phonophonie speak a spatial alphabet. Kagel calls for a spatial imagination of phonemes with the score.

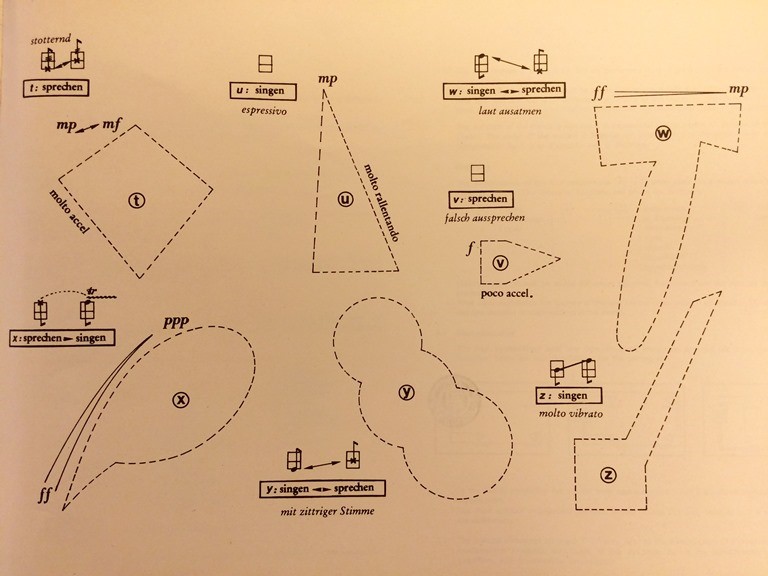

The mode between speaking and singing, between vocal gesture and bodily movement, creates what I would call “sound space.” This term does not simply suggest a physically localized sound in space, but also a physical bridge between voice and body. More specific to Phonophonie, one can consider the sound space the bridge between phonation of a syllable and phonation of a complete word, or equally, between a vocal “a” and a bodily gesture that articulates a similar “a.” More than complete words, Phonophonie proposes the phonation of letters and syllables, and the amplification of vocal effects and bodily movements. In this way, the score treats the voice as a cycle of density and expansion (see Fig. 1).

Fig. 1. Kagel asks the performer to vocalize the indicated letters both in extended and in expanded forms (Phonophonie, 53).

Kagel attempts to connect syllables with the position of mouth, considering it as a literal opening. Both the score and the performance suggest a similar sonic experience: hearing transitions between shapes and patterns, densities and volumes, timbre and pitch, and the extension and expansion of the voice. The sound spaces of the piece emphasize the sounds of the voice.

Kagel designates the sounds of the voice as “the most intense language”: “He has found a language…. He has found the language of the musical…which gives the most persuasive expression of his mute despair” (4). This is the only complete phrasing that Isherwood transmits with his “speaking voice.” Written as “oi…ax…n..o…au…” in the score, Isherwood’s vocal fragmentation intensifies the most intense language. The vocal fragmentation does not translate or represent a sign language, but performs the very life that happens in and through mouth. Mouth opens us to the rest of the body. This is what Phonophonie does. The opening resolves into physical and mental movement, which invites postural positioning and mental spacing. Isherwood’s mouth opens himself and the audience to his body from head to feet, and vice versa. The series of the performer’s bodily movements are carefully drawn out with this motivation.

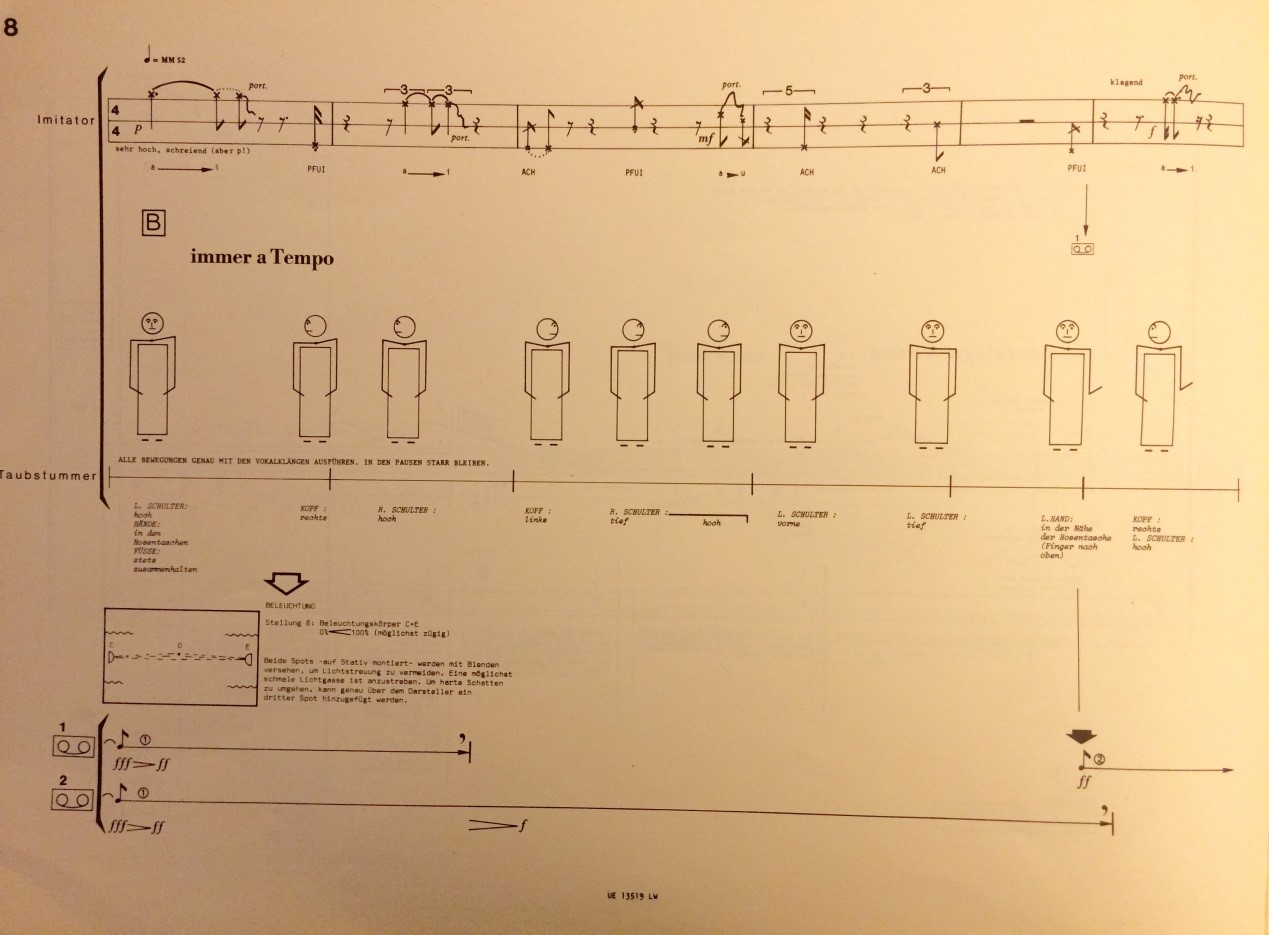

As shown in the score, Kagel repositions each persona and each voice with the movements (see Fig. 2). While repositioning the performer’s body, he also creates the spacing between the personas: one and the other may overlap each other, interrupt each other, conflict with each other, reinforce each other, repeat each other and, at the end of this cycle, they might transform each other—but they are not the same.

Fig. 2. Kagel re-locates the personas and voices with bodily movement (Phonophonie, 8).

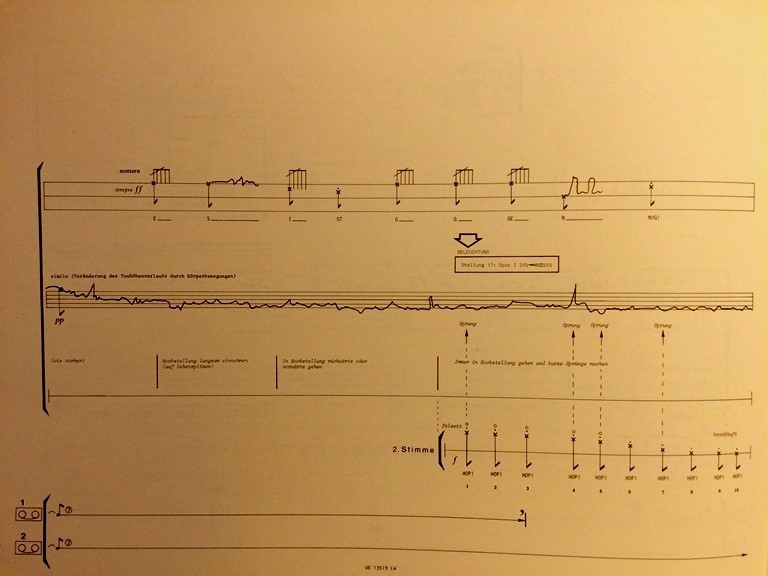

Kagel sketches the uniqueness of the personas musically. The mimic, marked as imitator on the score, performs an extended pitch. The ventriloquist’s part interrupts the mimic’s pitch with punctuated sounds. The singer, on the other hand, attempts to resolve the extended pitch into phrases and crystallize the division between the three voices. Towards the end of the bar, the deaf mute appears with a descending open note, slowing down the dense conversation between the mimic, the ventriloquist, and the singer (see Fig. 3). The dynamic between these personas is spacing that accents the limits between the parts and the voices. Thus the mimic, the ventriloquist, the singer, and the deaf-mute remain unique while transforming each other. Let us revisit this spacing in relation to syncopation, a deviation from the regular rhythm. Considering spacing, syncopation enables us to recognize the fast transitions between the personas on the score. Despite the uniqueness of the personas as sketched in the score, the vocal performance of the fast transitions complicates hearing the personas as distinct.

Fig. 3. The deaf mute appears with a descending open note, pacing the conversation between the mimic, ventriloquist and singer (Phonophonie, 26).

De-semiotization obliterates our preoccupation with and labels for each character. We cannot limit the personas when they’re translated into sound. Sound space, or specifically spacing as sound here, is a continuous, indistinct moment, a function that completes another unit. Imagine the four personas as four functions of sound. Even though they may have different names, they sound together. More significantly, they make sense when they sound together, since their existence is already partial and spatiotemporal. This pushes the conception of the voice beyond nominal codes and urges us to review its sound spaces as multiple.

If a sound space is the bridge between voice and body, and if sound spaces are multiple, then voice is a site of multiple sound spaces that has a specific corporeality and operates within a specific personal imagination. Such multiplicity and specificity are always in process. Though specific and multiple, a sound space is also common, shared by all. This configuration explains how, on the one hand, voice becomes a sonic interpellation of subjectivity, and how, on the other hand, it facilitates a medium of phenomenal exchange. The double-sidedness of the configuration does not allow us to objectify fully the meaning of the voice. Kagel exposes us to this double-sided configuration of the voice.

Let us consider Isherwood’s enactment of the voices in the piece. First, Isherwood oscillates between various voices that involve seemingly organic and effortless noises. To this end, Isherwood’s voice transcends his body as an everyday voice that operates with a tangible, communicable absence, with more immediacy, with less control and, in the end, with more unexpected resolutions and resistance against surfaces (bodies, spaces, etc.). Second, Isherwood consciously exaggerates, heightens, distorts, and mutes his vocalizations, creating disproportional images and noticeable sensory stimulation. In this way, Kagel violates the semantic content and easy access to the discursive juxtaposition between the four personas. Instead he draws attention to possible sonic affiliations between the personas. On the one hand, “this is only a play,” he states; on the other hand, he implies, “yet this play is more real than the real.”

Four voices and four personas generated by one single body are confusing: Who is who? Who says what? Perhaps, who is what? While vocalizing vowels, consonants and effect-like sounds, Isherwood presents an imaginary order, a possible narrative; yet at the same time he deletes the very narrative itself. The appearance and disappearance of the narrative affirms and realizes the becoming of the voice and of the personas. Phonophonie demonstrates the idea that voice cannot be completely reduced to one single name or character. In doing so, the piece exhausts “scandalous” speech, in Davidson’s words, by means of “hybrid combinations” (81). The fact that one single performer embodies these overstated and varied forms of speech demonstrates well the human body and self’s multiple ends, physically, psychologically, and socially. As such, the scandalous and hybrid combinations function even more profoundly, and the primacy of discursive language—or the abstraction of the logos from the voice—dissolves.[5]

Adriana Cavarero, in For More Than One Voice, discusses, on the one hand, the way that voice is reduced to logos at the expense of signification, and, on the other hand, the way that logos cannot be completely abstracted from the physicality of voice:

By capturing the phone in the system of signification, philosophy not only makes a primacy of the voice with respect to speech all but inconceivable; it also refuses to concede to the vocal any value that would be independent of the semantic.… Logos does allude to speech and involves vocalization. Not by chance does Aristotle define it as phone semantike. Although it is true that logos is generally reduced to a phonic signification, the voice still seems to anchor logos to a horizon in which there are mouths and ears, rather than eyes and gazes. (35, 40)

At the heart of this conflict, Cavarero sees the hierarchy of the senses and the primacy of sight over acoustics and sound. Examining these conceptions, she defends the embodied particularity of the voice. Similarly, deaf performance and the non-linguistic voice in experimental music unsettle the established logos of such hierarchy and expand on the idea of conceivable speech. How accountable is logos after all? Words and promises—they are broken, destined to fail. What remain are the modes and intensities of what is being said, of what is heard, and the delay between the two, which manifests acts of speech. Embodied particularity of the voice makes sense of such delays. In other words, embodiment of the voice authenticates and reciprocates the accidents of language. It makes the performative sensible.

Shoshana Felman’s book The Scandal of the Speaking Body wonderfully lays out the notion of the performative, its “scandalous coupling with promise” and intrinsically endemic “infelicity” (14-15). Creating a dialogue between Don Juan’s untruthful promises and J.L. Austin’s notion of the performative, Felman explains how it is that acts of speech cannot transmit truth but can only manifest a capacity to respond, to be adequate to contingencies. Austin defines performatives—such as “I apologize” or “I promise”—as utterances that cannot be descriptive or informative. Unlike constatives, they perform an act. Performatives are thus about “the success or failure” of an act, whether an act is fulfilled or not. Yet the question remains: To what extent can an act—a promise—be fulfilled or accountable? In response to this question, Felman draws a parallel between Don Juan and Austin:

Like Don Juan, Austin conceives of failure not as external but as internal to the promise…. That is why, like Don Juan, Austin suspects in his turn that the promise will not be kept, the debt not paid, the accounts not settled…. The performative doesn’t pay…. (45-46)

The performative is not supposed to pay. There is no accident of the performative. The performative is itself a rise and fall, an accident, a strain of the contingent.

I want to follow Davidson’s interpretation of the scandalous promise by suggesting the infelicity of the performative as an affirmative failure. My goal is not to champion failure as an affirmative conceptual category or as an ethical impossibility, but to think about the way that moments of failure—the accidents of the physical—can tangibly reveal the ways in which we speak to—become adequate to—contingencies. The embodiment of the voice—sonic, temporal, spatial, gestural, and affective knowledge of the voice—makes us embrace such moments within the delay between speaking and hearing. This awareness and practice, I argue, unsettle the normative thresholds of hearing, of logos, and of the limits of speech.

Conclusion: Silence and Speech

On the one hand, multiple sounds, silences, and voices in the Lecture on Nothing and Phonophonie mobilize, and on the other hand they bridge, the presumed distance between seemingly marginalized bodies. Such mobilization exploits the given limits of the human body and language, and thus enables us to imagine the syncope between different personas in the form of co-sounding. Catherine Clément’s astonishing reading of the “delay” of the “ego and its being” in her book Syncope: The Philosophy of Rapture recalls the “syncopated” transitions from one persona to another, from one voice to another. Clément describes syncopation much as I define sound space here, as an “absence of the self,” as a “cerebral eclipse,” and perhaps as a presence of the other (1). She writes:

But inside, what is going on? Where is the lost syllable, the beat eaten away by the rhythm? Where does the subject go who later comes to, “comes back”? Where am I in syncope? (5)

This article invites the reader to imagine the syncope—the co-sounding between different voices, silences, and sounds, between hearing and speaking. The side-by-side surface of silence and speech emerges between hearing and speaking. And the appearance and/or awareness of such syncope provides an opportunity to undo our normative attributions for deafness. In his famous essay, “The Normal and the Pathological,” Georges Canguilhem reminds us of the definition of anomaly as “an inequality, a difference in degree” (126). The definition of anomaly as a difference makes us question what constitutes the normal in the first place. Lecture on Nothing and Phonophonie offer a spectrum on which we can reflect and expand on the presumption of the so-called normal voice and the normal hearing body. Furthermore, following Canguilhem’s definition, both pieces allow us to hear a deaf voice not as pathology but as difference, and difference as a function of similarity. Without turning a deaf voice into an idealized, fetishized, unmarked, or neutralized category of silence or speech, both lead to the possibles of speech and silence, that is, to the emergence of it as something possible.

Zeynep Bulut is a Lecturer in Music at King’s College London. Her most recent publication, “Singing and a song: The Intimate Difference in Susan Philipsz’s Lowlands,” appeared in the volume Gestures of Music Theatre: The Performativity of Song and Dance (Oxford University Press, 2014). Her monograph, Skin-Voice: Contemporary Music Between Speech and Language (in progress), examines the nonverbal voice in experimental music and sound art as skin, as a point of contact and difference between self and the external world.

Footnotes

[1] For example studies on opera and melodrama such as Abbate, Smart, and Poizat.

[2] Some highlights include Barthes, Derrida, Ihde, Connor, Dolar, Weiss, Ronell, and Cavarero.

[3] Jonathan Sterne draws attention to David Mitchell and Sharon Snyder’s notion of “narrative prosthesis.” Sterne summarizes this notion as follows: “David Mitchell and Sharon Snyder call a ‘narrative prosthesis,’ where the stigmatized, pathologized figure of a person with a disability is used to advance a narrative, usually a metaphor for something else” (20). Also see Mitchell and Snyder.

[4] Auslander here refers to Richard Schechner’s definition of performance as “a twiced behaved behavior” (169).

[5] See Cavarero 35, 40. See also Dolar, especially the chapter “Kafka’s Voices,” pp. 164-189.

Works Cited

- Abbate, Carolyn. In Search of Opera. Princeton: Princeton UP, 2001. Print.

- Auslander, Philip. “Performance as Therapy: Spalding Gray’s Autopathographic Monologues.” Bodies in Commotion: Disability and Performance, Eds. Carrie Sandahl and Philip Auslander. Michigan: U of Michigan P, 2005. 163-175. Print.

- Auslander, Philip and Carrie Sandahl. “Disability Studies in Commotion with Performance Studies.” Bodies in Commotion: Disability and Performance. Eds. Carrie Sandahl and Philip Auslander. Michigan: U of Michigan P, 2005. 1-13. Print.

- Barthes, Roland. The Grain of the Voice: Interviews (1962-1980). Trans. Linda Coverdale. New York: Hill and Wang, 1985. Print.

- Brikema, Eugenia. “Critique of Silence.” differences: A Journal of Feminist Cultural Studies. Eds. Rey Chow and James Steintrager. 22.2-3 (2011): 211-235. Print.

- Cage, John. “Lecture on Nothing.” Silence: Lectures and Writings. Middletown: Wesleyan UP, 1961. 109-127. Print.

- Canguilhem, Georges. “The Normal and the Pathological.” Knowledge of Life. Eds. Paola Marrati and Todd Meyers. Trans. Stefanos Geroulanos and Daniela Ginsburg. New York: Fordham UP, 2008. 121-134. Print.

- Cavarero, Adriana. “How Logos Lost Its Voice.” For More Than One Voice: Towards a Philosophy of Vocal Expression. Trans. Paul A. Kottman. Stanford: Stanford UP, 2005. 19-79. Print.

- Connor, Steven. Dumbstruck: A Cultural History of Ventriloquism. Oxford: Oxford UP, 2000. Print.

- Clément, Catherine. Syncope: The Philosophy of Rapture. Trans. Sally O’Driscoll with Deirdre M. Mahoney. Minneapolis: U of Minnesota P, 1994. Print.

- Davidson, Michael. Concerto for the Left Hand: Disability and the Defamiliar Body. Ann Arbor: U of Michigan P, 2008. Print.

- —. “The Scandal of Speech in Deaf Performance.” Signing the Body Poetic: Essays on American Sign Language Literature. Eds. H. Dirksen, L. Bauman, Jennifer L. Nelson, and Heidi M. Rose. Berkeley: U of California P, 2006. 230-248. Print.

- Davis, J. Lennard. “Deafness and Insight: Disability and Theory.” Enforcing Normalcy: Disability, Deafness and the Body. New York: Verso, New Left Books, 1995. 100-126. Print.

- —. “Introduction: Disability, Normality, and Power.” The Disability Studies Reader. Ed. Lennard J. Davis. New York: Routledge, 2013. 1-17. Print.

- Derrida, Jacques. Speech and Phenomena: And Other Essays on Husserl’s Theory of Signs. Trans. David B. Allison. Evanston: Northwestern UP, 1973. Print.

- Dolar, Mladen. A Voice and Nothing More. Ed. Slavoj Zizek. Cambridge: MIT P, 2006. Print.

- Felman, Shoshana. The Scandal of the Speaking Body. Stanford: Stanford UP, 2002. Print.

- Friedner, Michele and Stefan Helmreich. “Sound Studies Meets Deaf Studies.” Senses and Society 7.1 (2012): 72-86. Print.

- Goodman, Steve. “The Ontology of Vibrational Force.” The Sound Studies Reader. Ed. Jonathan Sterne. New York: Routledge, 2012. 70-73. Print.

- Heile, Björn. The Music of Mauricio Kagel. Burlington: Ashgate, 2006. Print.

- Ihde, Don. Listening and Voice: A Phenomenology of Sound. Athens: Ohio UP, 1976. Print.

- Kagel, Maurizio. Phonophonie. 1963/64. London: Universal Edition, 1976.

- LaBelle, Brandon and David Kurs. “Lecture on Nothing.” Liner Notes. Lecture on Nothing. Errant Bodies Records, 2010. CD.

- Mills, Mara. “On Disability and Cybernetics: Helen Keller, Norbert Wiener, and the Hearing Glove.” differences: A Journal of Feminist Cultural Studies. Eds. Rey Chow and James Steintrager. 22.2-3 (2011): 74-112. Print.

- Mitchell, David T. and Sharon L. Snyder. Narrative Prosthesis: Disability and the Dependence of Discourse. Ann Arbor: U of Michigan P, 2001. Print.

- Padden, Carol and Tom Humphries. Inside Deaf Culture. Cambridge: Harvard UP, 2005. Print.

- Poizat, Michel. The Angel’s Cry: Beyond the Pleasure Principle in Opera. Trans. Arthur Denner. Ithaca: Cornell UP, 1992. Print.

- Rée, Jonathan. I See Voices: Deafness, Language and the Senses. London: Flamingo, 2000. Print.

- Riefe, Jordon. “Q&A: Robert Wilson on Performing John Cage’s Lecture on Nothing.” Blouin Artinfo. Louise Blouin Media. 16. Oct. 2013. Web. 27 Jul. 2015.

- Ronell, Avital. The Telephone Book: Technology, Schizophrenia, and Electric Speech. Lincoln: U of Nebraska P, 1989. Print.

- Sandahl, Carrie and Philip Auslander. “Disability Studies in Commotion with Performance Studies.” Bodies in Commotion: Disability and Performance. Eds. Carrie Sandahl and Philip Auslander. Ann Arbor: U of Michigan P, 2005. 1-13. Print.

- Siebers, Tobin. Disability Theory. Ann Arbor: U of Michigan P, 2008. Print.

- Smart, Mary Ann. Mimomania: Music and Gesture in Nineteenth-Century Opera. Berkeley: U of California P, 2004. Print.

- Sterne, Jonathan. “Part 1: Hearing, Listening, Deafness.” The Sound Studies Reader. Ed. Jonathan Sterne. New York: Routledge, 2012. 19-23. Print.

- Weiss, Allen. Breathless: Sound Recording, Disembodiment and The Transformation of Lyrical Nostalgia. Durham: Duke UP, 1995. Print.