Global Pictures: Formalist Strategies in the Era of New Media

| November 25, 2018 | Posted by Webmaster under Volume 25, Number 2, January 2015 |

|

Krista Geneviève Lynes (bio)

Concordia University

Abstract

This essay examines the role played by political and activist media, as well as media infrastructures and platforms, in creating solidarity or continuity between the Arab Spring, the Occupy Movement, Indignados and the ‘Printemps Erable,’ among others. It critiques the overvaluation of social media in organizing protests and creating solidarity between social movements, demonstrating the renewal of discourses of the “global village” on which such valuations depend. Instead, it examines the role of aesthetics in creating sites of solidarity and affiliation across different local political struggles, taking as its case study a series of performances and a video work by the artist Milica Tomic.

The Arab Spring, the Indignados movement, the printemps érable, Occupy Wall Street, and the proliferation of “occupations” in 2011 and 2012 have enlivened critical and aesthetic discourses about social movements. The irruption of protests in disparate parts of the globe has invited questions about the possibilities of solidarity across national and regional divides, and the role that media (new and old) might play in circulating powerful symbols of protest transnationally and in building transnational networks that support local protest struggles. Amateur footage from local protests, the dissemination of poster art or photographs of victims of police violence through social media networks,[1] performances that draw attention to the acute forces of power and exploitation, “hacktivist” actions, and activist art all contribute to mediatizing and mediating protest movements, intervening in public culture, and creating iconic images that migrate from specific protest sites to politically engaged publics around the world.

The circulation of images of protest; connections through social media platforms such as YouTube, Facebook, and Twitter; and the “occupation” of public space have led to the search for what W. J. T. Mitchell, following Heidegger, calls a “world picture,” a dominant global image linking the Occupy movement, the Arab Spring, and European uprisings, as well as a methodology that accounts for the “infectious mimicry” between, for instance, Tahrir Square and Zuccotti Park (Mitchell, “Image” 8). Questions emerge, first, about the contiguity of the movements through media infrastructures and platforms, in the use of imagery, and in the language of protest, and second, about the mediating role of activists and cultural producers, broadly speaking, in framing protest and demanding structural change.

While much has been made of the sociality of “social media” (its capacity to connect within and across protest movements), it has also highlighted distinctions between protests in different parts of the globe. Such distinctions are material— the “hard” revolutions of Tahrir Square (demands for the fall of autocratic regimes, democracy, civil liberties, and a “decent Keynesian economy”) versus the “soft” revolutions of Zuccotti Park (a radical critique of American capitalism rather than of the state, per se)—but also aesthetic, contrasting the perceived “excesses” of protest culture in North America with the social realist genre of protest languages in the Arab Spring. While the aestheticization of political action has been suspected when it comes to the representation of material demands, corporate media structures such as Twitter have frequently been celebrated in mass culture as having “world picture”-making potential.

The dismissal of “excessive” media tactics in North American cities has taken the form of accusations that the social movements are in fact nothing but representation, in other words that protestors’ demands are simulacral, or that the movements exist more fully as declarations of resistance than as instantiations of it. Protesters have donned top hats and pig snouts, rolling around in piles of fake bills to highlight the obscene actions of corporate executives.[2] Anonymous and LulzSec, among other groups, playfully threatened to erase the New York Stock Exchange from the Internet (Penny). Activist artworks, such as the fictive National Agency for Ethical Drone-Human Interaction’s “Do Not Kill Registry,” mocked the democratic potential of government sites for civic engagement. Drum circles, “chalk walks,” “favela cafés,” and other performative actions used cities as a staging ground for ongoing protests.[3]

A banner example of the accusation of frivolity and excess is a New York Times column from 23 September 2011 by Ginia Bellafante, which described Occupy Wall Street as an “opportunity to air social grievances as carnival,” and gave a vivid account of a protestor, “half-naked,” bearing a “marked likeness to Joni Mitchell and a seemingly even stronger wish to burrow through the space-time continuum and hunker down in 1968.” Bellafante’s colorful description at once summons an image of the carnivalesque character of protest culture and public intervention and ties such excesses to anachronistic forms of political action, to a retrograde hippie culture that occluded, for Bellafante, the very real facts of rising income inequality.

Defenses of the Occupy movement have felt the need also to distance themselves from such performative excesses. For instance, a frequently circulated rebuttal to this article, Allison Kilkenny’s “Correcting the Abysmal ‘New York Times’ Coverage of Occupy Wall Street,” argues that Bellafante’s focus on “strange and inarticulate individuals” occludes not only the real people (without jobs, concerned about their future) but also the reality of police violence, the erosion of leftist organizations, and corporate support for right-wing protest spectacles (such as the 2012 “town hall” events). Kilkenny’s contrast between the real threats of violence faced on the left and the spectacles of outrage on the right signals a doubt that the performative and the poetic can address real suffering in times of crisis.

The presumed privilege of New York-based activist artists vis-à-vis the foreclosed publics of the US financial crisis is mirrored by the privilege of North American and some European protest movements in contrast with the uprisings of the Arab Spring. If North American and European protestors are tarred with the accusation of aesthetic decadence—a decadence indicated by the representational regime that is mobilized in various street protests in American cities—their politics are marked in contrast with the presumed realism of the languages of protest in the Arab Spring and elsewhere. Activists in North America and Europe may then—by virtue of their languages of protest and mediatized spectacles—be in a position of misplaced solidarity with disenfranchised groups in other parts of the world. The role of media as both means of representation and apparatuses of circulation (the “connectivity” brought into focus by, for instance, the reliance on Facebook and Twitter to organize in Egypt and elsewhere) might then be contrasted with the disjunctures between the material conditions of cultural producers in different parts of the globe. As W.J.T. Mitchell asserts, “Tangier is not Cairo is not Damascus is not Tripoli is not Madison is not Wall Street is not Walla Walla, Washington” (“Preface” 3).

And yet, Mitchell poses the question, “How can one bring into focus both the multiplicity and the unity of this remarkable year? What narrative would be adequate to it?” (“Preface” 3). Mitchell notes that, while in the nineteenth century, metaphors of hauntings and revenants marked descriptions of European politics, the contemporary moment is replete with metaphors of contagion to describe the “viral” processes of global media (“Preface” 4). Readings of Arab Spring protests are attuned to the use of global forms and icons. For instance, Sujatha Fernandes makes the point that rap songs have

played a critical role in articulating citizen discontent over poverty, rising food prices, blackouts, unemployment, police repression and political corruption. Rap songs in Arabic in particular—the new lingua franca of the hip-hop world—have spread through YouTube, Facebook, mixtapes, ringtones and MP3s from Tunisia to Egypt, Libya and Algeria, helping to disseminate ideas and anthems as the insurrections progressed.

Many articles have stressed the manner in which organizing and political expression have relied on social media sites and blogs to render experiences of state violence and disenfranchisement, and to voice political opposition. Facebook and YouTube have served as engines for the galvanization of communities around social injustice, as for instance with the Facebook page “We Are All Khaled Said,”, a page that posted family portraits of the Egyptian businessman who was pulled from an Internet café by two police officers and beaten to death, alongside cellphone photos from the morgue of his battered and bloody face. The page not only provided updates about the case, but also helped spread the word about demonstrations, and documented protests from the street.

Thus, while media platforms are viewed as enabling technologies, permitting the circulation of media locally and transnationally and affecting the organizational capacity of grassroots movements, the representational regime of protest is marked by the disjunctures noted above between a bourgeois or nostalgic avant-garde and a political art “by any means.” Indeed, Boris Groys makes the argument that only propaganda (he cites among his examples Islamic videos or posters functioning in the context of antiglobalist movements) can be politically effective because it does not follow the logic of the market (7). The material conditions of cultural production in spaces of protest—and the opening of sites of circulation and solidarity—are central to identifying spaces of contact under the uneven conditions of globalization. The disjunctures between national social contexts, the languages of protest, sites of agency, and the uses of media are central to accounts of media cultures in a globalized present. Of interest to this study, however, is the bifurcation between a critique of the differential languages of protest around the globe and a celebration of the circulatory force of social media in binding communities of protest, if not in a common language, at least in the dream of a common purpose.

In this regard, Kay Dickinson cautions that while bloggers and Tweeters such as Slim Amamou in Tunisia and Sandmonkey (Mahmoud Salem) in Egypt briefly entered official channels of political representation, these “movers and shakers of the so-called Facebook revolution are not, in the end, the faces assuming orthodox political power, perhaps because that platform does not boast particularly high per capita penetration in Egypt” (132). In many countries of the “Arab Spring,” Dickinson stresses, existing relations between the state and media have persisted, amateur reportage has been discredited, and profits have continued to accrue for companies such as YouTube. The focus on the use of social media, including the visual regime of camera phones and YouTube videos, obscures these material relations, drawing instead a figure of a global media landscape on the anachronistic model of the “global village.”[4] The neutrality of new media technologies is guaranteed in celebrations of the twenty-first century “global villlage” by their function as a platform for action or a ground for political activity. The focus on the role of social media has thus concentrated more fully on the number of publics they touch, and thus their “spreadability,” rather than their political economy or their structuring of online public space (Jenkins, Ford, and Green 3).

The focus on the mobility of images and the use of social media platforms to organize protests and galvanize sentiments for political change accordingly reanimates McLuhan’s mid-twentieth-century fantasy of the global village for analyzing the transnational or global dimensions of media. The return of McLuhan’s metaphors (if not his language) in the discourse of new media points to the coincidence between the development of new corporate structures and McLuhan’s vision of the power of mass media to specialize and rechannel “human energies,” even though the ideal community McLuhan traced in his texts never materialized (McLuhan 125). As such, McLuhan’s articulation of the “extensions of man” returns precisely because it describes the networked qualities of capital and allows for economic developments in media infrastructures to be coded erroneously as new forms of collectivity and public space (McLuhan and Powers 83).

McLuhan’s early diagnosis of the extensions of the human through communications technology in some respects shapes current discourses about media’s globalization. It also maps the new oligopolistic circuits of capital that serve as a propulsive force both for the infrastructures and circuits through which media contents migrate, and for icons with translative potential. McLuhan saw the information economy as a mechanism for extending consciousness beyond a single time and place. He states:

Video-related technologies are the critical instruments of such change [to a marketing-information economy]. […] The new telecommunication multi-carrier corporation, dedicated solely to moving all kinds of data at the speed of light, will continually generate tailor-made products and services for individual consumers who have pre-signaled their preference through an ongoing database. Users will simultaneously become producers and consumers. […] Culture becomes organized like an electric circuit: each point in the net is as central as the next. Electronic man loses touch with the concept of a ruling center as well as the restraints of social rules based on interconnection. Hierarchies constantly dissolve and reform. (McLuhan and Powers 83-92)

The scale of the global is fruitful in that it poses political economy as a problem of media circulation beyond local and national frameworks, “in the light of the complexities of contemporary relational geographies of power” (Grossberg 59). Critical engagements with the global dimensions of media circulation are not meant simply to obscure the poignancy of the “global village” (in its material dimensions and as a powerful fantasy of interconnection). McLuhan foresaw that the processes of interconnection and decentralization were neither irreversible nor exhaustive. He was sensitive both to the agglutinations that produced, in his terms, new “tribalisms,” and the constant processes of enhancement, obsolescence, retrieval, and reversal that he called the “tetrad” (McLuhan and Powers 9-10).

The trouble for analyses of the liberatory potential of new media in the contemporary moment lies not in McLuhan’s diagnoses of the extensions of humankind through media, but rather and especially in McLuhan’s articulation of the liberatory potential of the global village. For McLuhan, the global village produces a vacillation between what he called “visual” and “acoustic” space, between figure and ground, that extends beyond hierarchical systems of power toward lateral networks across space. He calls this vacillation a “resonating interval,” produced in his example by the images people saw of the earth taken by the Apollo astronauts in 1968, and in the experience of simultaneously being on the earth and on the moon, of being, effectively, in the “airless void between” (McLuhan and Powers 4).[5] McLuhan’s “resonating interval” involves a chiasmic vacillation: technologies come into view, recede into obsolescence, are retrieved as melancholic objects, and reverse back into ground. For McLuhan, “the new video-related technologies promise to impose a new monopoly of ground over figure. Whatever is left of mechanical age values could be swallowed up by information overload” (McLuhan and Powers 11).

The idea that globalized media platforms such as Twitter and Facebook are the ground for local incidences of social struggle has reinforced McLuhan’s vision of the resonating interval, along with its metaphors of an “airless void” and of the monopoly of ground over figure. In light of the differential and historically specific uprisings around the globe, it is important for critical accounts of media’s “spread” to bring into focus the particular conjunctures of space and time mediated in culturally dominant and experimental forms, along with the representation of relations of figure and ground, especially under the current climate of economic crisis and political protest. For while new media is joined to the spatial figuration of the “global village,” both the crises and failures of market structures in the twenty-first century and the (still speculative but generative) coincidences between forms of social protest around the globe signal different configurations of space and time that are less bound by the tropes of simultaneity and broadcasting than by concerted, politically engaged signifying practices in specific translocal sites.

Rather than understanding this translocality as the “global village,” then, how might we see global processes as overlapping and competing geographies, with their different logics of boundaries, connectivities, and stratifications (Grossberg 60)? The very scale of the global demands an imaginative leap across specific instances in the interest of a critical scholarship that understands and engages the effects of worlding, in the interest of forging sites of solidarity and resistance. Such scales of analysis (in media, activism, and academics) focus on questions of production and reception in cultures of exchange, attending specifically to the differential relationships in the global system and the uneven terms of cooperation, even as the aim of scholarship and cultural production remains to discover possibilities for alliances, alternative histories, or new identity positions. This approach is guided by the challenge that Anna Tsing poses for scholars: “freeing critical imaginations from the specter of neoliberal conquest—singular, universal, global” (77). She argues that “attention to the frictions of contingent articulation can help us describe the effectiveness, and the fragility, of emergent capitalist—and globalist—forms” (77). This challenge refocuses our attention on the emergent forms of media practice, on migratory aesthetic strategies, images, and symbols, as well as on the distinct historical nature of cinematic and political strategies. How might committed artistic strategies engage the complexities of time and space in the current conjuncture without conceding to a homogeneous and continuous vision of the globe (or of progress)? What other avenues for unity and collectivity exist in and through processes of mediation? The potency embodied in the reach of the uprisings around the world—and in their references to historical moments of revolutionary potential—begs the questions both of the (geographic and historical) connections between social struggles, and of the role that media play in the McLuhanite processes of extension and, conversely, of the singularity of visual cultures.

To engage these questions, I turn to a video work and performance by the Belgrade artist Milica Tomic, entitled One day, instead of one night, a burst of machine gun fire will flash, if light cannot come otherwise (Oskar Davico—fragment of a poem) (2009). The artwork provides a complex example of the mediations between social struggles in disparate locations and moments, and of the role that historical languages play in figuring the space of the globe as a world-making activity, by interrogating the historical possibility of revolutionary action in the contemporary moment with a reenactment of anti-fascist actions in Belgrade in World War II. It also poses the question of the spatial dynamics of revolutionary unity through a dedication (which appears in the video) to the “Belgrade 6” (a group of political activists associated with the Anarcho-Syndicalist Initiative, the Serbian section of the International Workers’ Association, who vandalized the Greek Embassy in Belgrade in solidarity with Thodoros Iliopoulos, who was imprisoned for protesting police abuse and corruption in Greece in 2008). In posing questions about the spatial and temporal contiguity of revolutionary actions, Tomic’s work theorizes a ground for global pictures that is alternative to the metaphor of the global village, one that places the global village under erasure as part of its politics of representation.

In the video, Tomic records her passage, with a machine gun in hand, through several sites in Belgrade where the People’s Liberation Movement carried out successful actions against Nazi occupation during World War II. The scenes are combined both through the spatial contiguities in the work’s montage, and through the video’s soundtrack, which includes excerpts of five interviews with partisans who participated in the liberation of what would become the Socialist Federal Republic of Yugoslavia. In viewing the documentation, the viewer becomes immediately aware of the incommensurability of the scenes recorded in the performance. For instance, the video begins with Tomic walking down a residential street in the direction of the camera. As she crosses the street to turn right, her continuous movement is severed by her appearance in a different section of Belgrade, passing in front of a small antique shop. As the video progresses, the path traced by Tomic brings into view pedestrian crossings, train tracks, bus stations, busy commercial centers, and residential streets. While her movement appears nominally continuous from scene to scene, therefore, the path Tomic traces through the city of Belgrade is constituted out of a series of videographic fragments, stitched together through montage to form an “artificial landscape” (Kuleshov 51).

The formal aesthetic of One Day draws from neither the languages of telecommunications technology nor the immediate intimacy of social media but from the structuralist film theory of early twentieth-century Russian filmmaker Lev Kuleshov. Kuleshov devised his montage technique while shooting Engineer Prite’s Project (1917-18), after he neglected to film shots of his actors looking at electric poles. He solved this predicament by splicing shots of his actors looking off-camera with separate shots taken of rows of electric poles in a different part of Moscow. Based on this, Kuleshov articulated a theory of montage according to which the synthesis of fragmentary shots can create a visual terrain that exists nowhere in reality. He called the resulting filmic landscape an artificial landscape or creative geography (51).

One aim of formalist cinema in the 1920s was to create new modes of aesthetic perception by dismantling and reconstructing traditional art forms. Formalists and futurists of Russian cinema were engaged in developing a materialist analysis of art as a system of signs. Language was thus viewed as “concrete,” materialist, and mass-oriented, and consistent with materialist interpretations of history (Kuleshov 27). The capacity to “synthesize” an artificial landscape was certainly a formal cinematic device, but it also served several synthetic fantasies for Kuleshov: his geopolitical suturing of the American White House to shots of a well-known building in Moscow; his synthesizing of a filmic female body by combining separate shots of several women’s bodies, cut to the measure of desire (Mulvey 46); and, most famously, his suturing of the viewer to the actor Mosjoukin’s affective response through a shot-counter-shot sequence known as the Kuleshov effect.

Movement, for Kuleshov, characterized cinematic duration, and a screen action had to conform to the montage of a particular sequence in order to be locked into the structure of the film. For the director, “montage creates the possibility of parallel and simultaneous actions, that is, action can be simultaneously taking place in America, Europe, and Russia, that three or four or five story lines can exist in parallel, and yet in the film they would be gathered together in one place” (Kuleshov 51). The associational power of montage resides in the viewer’s consciousness, with no necessary relation to “objective reality,” and thus ran counter to Soviet-era concerns with “objective” themes and truths. Kuleshov’s formalism aimed in fact to create new modes of aesthetic perception by derogating, dismantling, and reconstituting art forms. The assemblage of signs (here of different locations in an “artificial landscape”) provides the structure for the material and value systems of artistic discourse.

Tomic’s record of her public intervention refers to Kuleshov’s formalist cinematic technique, and is thus allied to revolutionary artistic practice from the early twentieth century rather than to the documentary conventions of performance art or the technologies or techniques of new media that are the focus of most contemporary articulations of the “global village.” Tomic’s use of Kuleshov’s technique disrupts the viewer’s expectations of the aesthetics of global media, and interrupts the flows of media constitutive of the foreshortening of global space. The mobilization of Russian formalism as a political strategy in the contemporary period, however, also interrupts the futurist impulse of such experimentation. After all, how might a practice that evokes the archaism of streams of celluloid on the cutting room floor engage the materialism of contemporary globalization, except perhaps by negation?

One Day uses Kuleshov’s montage technique to make various sites in Belgrade, sites of historical acts of resistance and political struggle, appear to constitute a single location over a continuous period of time. Initially, such continuity seems to tend towards McLuhan’s concept of a resonating interval, in which the distance between places is collapsed. These aesthetic strategies, however, are mobilized to pose questions about the temporal and spatial coincidence of revolutionary events and revolutionary aesthetic styles, particularly given the difficulty of assuming a synthesizing activity in the viewer, for whom incommensurability may trump the divination of a foundational structure of revolutionary action.

The different locations are encountered several times in the video. Tomic moves frequently to and fro, in rhythmic patterns across the sites. Here Kuleshov’s montage technique foregrounds not the seamlessness of space mediated by technologies of representation, but the act of synthesizing political actions, and the dependence of such synthesis on the metaphors of a continuous landscape or ground from which actions spring. In narrowing the (spatial) gap between resistance actions, Tomic creates a landscape of revolt where action follows upon action; the defamiliarization of scenic juxtapositions, however, also defers the continuity of the landscape in the contemporary moment, a moment marked not by the unified actions of anti-fascist struggle but by the unstable question of revolutionary action against the decentralized and largely virtual power of global capitalism, witnessed in the trades in derivatives and complex debt obligations that caused the financial crisis in 2008.

One might recall, by contrast, the absence of ground in the canonical early video by Nam June Paik, entitled Global Groove. In this video, a swirling pastiche of dancers (moving to American rock, Japanese, and Korean music), a Navajo woman singing and beating a drum, a Japanese television spot for Pepsi, and interviews with Allen Ginsberg and John Cage all float in the seamless and distributed electronic space of broadcast television. The overlay of different images suggests the multitudinous information flows of the age of globalization, but also the cross-cultural encounters enabled by the medium of broadcast television. Paik distorted the televisual medium with colorizing, video feedback, magnetic scan modulation, and nonlinear mixing to generate not only a properly videographic aesthetic style, but also a rendering of telecommunicative space on the model of the resonating interval, which is to say, as electronic space rather than as creative geography.

One Day, on the other hand, not only reproduces the realism of figure/ground relations in the representational conventions of indexical media, it also renders her action through a historically-inflected cinematic space. The video thus reflects (and reflects upon) an historical moment in which the impression of reality is constructed through the realization of a coherent space constituted, according to Stephen Heath, “in movement, positioning, cohering, [and] binding in … a coding of relations of mobility and continuity” (26). Pierre Francastel notes evocatively that

spaces are born and die like societies; they live, they have a history. In the fifteenth century, the human societies of Western Europe organized, in the material and intellectual senses of the term, a space completely different from that of the preceding generations; with their technical superiority, they progressively imposed that space over the planet. (qtd. in Heath 29)

Modern cinema performed a synthetic function tied to the development of modernity itself and its spatial paradigms: it confirmed a monocular perspective and the positioning of the spectator-subject through an identification with the camera at the point of a centrally embracing view. The movement of figures in a film, the camera’s movement, and the movement from shot to shot hold film within a certain vision, unfolding a vision of the world as and in space, and at the same time hold the possibility of radically disturbing that vision, through “dissociations in time and space that produce contradictions of the alignment of the camera-eye and the human-eye in order to displace the subject of the social-historical individual into an operative—transforming—relation to reality” (Heath 33).

Movement is central to cinematic language; from the outset, human figures figured movement in film by spilling out of the train or leaving the factory. As Heath argues,

The figures move in the frame, they come and go, and there is then need to change the frame, reframing with a camera movement or moving to another shot. The transitions thus effected pose acutely the problem of the filmic construction of space, of achieving coherence of place and positioning the spectator as the unified and unifying subject of its vision. (38)

It is only through “trick effects” (eyeline matching or the 180-degree rule, for instance) that space is ever perceived as unitary.

The exposure of creative geography in Tomic’s work is meant to exacerbate the tension between fragmentation (the dispersal of the video into separate scenes that do not match up) and unification (the positing of a properly cinematic narrative space). In citing Kuleshov’s montage aesthetic, Tomic allies her performative intervention not with the “airless void” of much new media work, but rather with the mystification that transforms the fragments of shots constituting a film into the narrative coherence of cinematic space. The creation of space in the contemporary moment (and the flattening of historical frameworks in the simultaneity of global flows) thus occurs only through a synthetic action, one that discounts the discontinuities within globalizing processes. In cinematic space,

Frames hit the screen in succession, figures pass across the screen through the frames, the camera tracks, pans, reframes, shots replace and—according to the rules—continue one another. Film is the production not just of a negation but equally, simultaneously, of a negativity, the excessive foundation of the process itself, of the very movement of the spectator as subject in the film. (Heath 62)

Tomic’s use of the method of artificial landscape does not only reference the formal cinematic constitution of synthetic space. One Day also allies the development of revolutionary aesthetic languages with the development of revolutionary political praxes in the early twentieth century. The testimonies of the partisans of the People’s Liberation Movement on the video’s soundtrack are—like the scenes and actions—stitched together out of numerous interviews to allegorize an account of political struggle and emancipatory politics in the anti-fascist struggles of the 1940s. Taken together, the interviewers’ statements provide a multivocal account of the development of political consciousness, on the one hand, and of a political movement, on the other. The voice-over begins with the statement, “If I were born again, I would follow the same path,” thereby allegorizing Tomic’s movement through the film as a choice to take part in resistance, to take the path of revolutionary action. Tomic’s choice to begin and end the voice-over with the same statement also figures the narrative logic of return that synthesizes the testimonies and Tomic’s intervention in a meaningful inquiry into modes of political action.

The interviewers emphasize the work of collaboration, of synthesizing a social movement out of the resistance to occupation:

There was a strong popular resistance to occupation. The Communist Party read this perfectly. It sensed that people were ready to fight against the occupation, for a better life. We did not introduce the Republic then, nor excluded the Monarchy. There were royalists among the partisans; there were Christians, Muslims, believers, non-believers, but they were all anti-fascists. That was the key! People realized that they were only joining the struggle against evil. Partisans and partisan units came into being not as a Communist Party army, nor as any party’s army, but as the army of the PEOPLE.

The montage technique in the video accordingly serves not only to figure a creative geography of resistance, but also to figure that landscape in the service of the work of building political solidarity. The move is not simply nostalgic, mourning a taken-for-granted universalism, but also articulates what anthropologist Anna Tsing calls “universal aspirations” (1). On what grounds, through what forms of solidarity and mediation, might social movements conceptualize the global, even as a fiction or imaginative act, outside the global village? Drawing from Gayatri Spivak’s compelling statement that “we cannot not want the universal, even as it so often excludes us,” Tsing argues for the theorization of global connection through what she calls “generalization” from small details, a generalization that involves, first, a unification of the field of inquiry through “spiritual, aesthetic, mathematical, logical or moral principles” and, second, collaboration among different knowledge-seekers that turns disparate forms of knowledge into compatible ones (89). Such collaboration involves the patient, provisional work of bridging and negotiating across incompatible differences.

Tsing’s focus on the friction between unification and generalization, on the one hand, and collaboration and negotiation, on the other, helps shed light on claims to the global character of media cultures that frequently take the ground of contact (media technologies or platforms, for instance) as the generalizable universal (different cities but Twitter revolutions nonetheless …) and that consider images, aesthetic strategies, performances, and slogans as involving the work of bridging and negotiation. For Tsing, the unification of a field of inquiry requires not simply the continuity of a media platform, but also the concerted work of generalizing from details (hence the continuity of common technologies, certainly, but also of efforts at creating iconic figures or common languages). Similarly, concerted efforts at a complex and emancipatory unity across local sites of social struggle require not only the work of translation across idioms, but also the material connectivity that allows images and symbols to circulate translocally.

Tsing’s central point is that both features of generalization—unification and collaboration—mask one another: “The specificity of collaborations is erased by pre-established unity; the a priori status of unity is denied by turning to its instantiation in collaborations” (89). The focus on social media as the ground for actions across the globe erases the work of translation and transcoding required for producing solidarity across different positions in the global system. Conversely, the focus on incommensurability denies the complex spread of revolutionary languages and action across the world since 2011. It is, in fact, the very interplay of universalization and negotiation that constitutes and figures the global scale in its complexity. Rather than resolving this tension, Tsing uses the term friction to describe the unstable, unequal, and creative forms of interconnection across difference. She notes, “Friction reminds us that heterogeneous and unequal encounters can lead to new arrangements of culture and power” (5).

Her method: ground the work of universalizing in specific historical contexts, through the unstable and shifting arrangements of power/knowledge in the global system; likewise, frame the work of negotiation and collaboration in the aspirational and unfulfilled imaginary of a (perpetually unachieved) universalism (Lynes). The work of encounters across difference in the world thus becomes a model for critical and cultural production, the careful theorization of discrepant conjunctures rather than a single-minded cultural explanation. With respect to global pictures, the figure of friction similarly figures the work of representation in and across local contexts. Not only is Tahrir Square not Zuccotti Park, but Facebook in Cairo is not Facebook in New York. Social media produced blogger-activists and the Syrian Electronic Army;[6] the slogan “Occupy Everything” functioned teleopoietically to call forth a universal aspiration that had great mobility across anti-capitalist struggles worldwide; the printemps érable in Montréal in 2012 transcoded the printemps arabe through the semiotic slippage of near-homonyms to signal the continuity of the Québec student struggle with the larger revolutionary struggles around the world. There are “resonating intervals” in all these cases, but they are marked by friction rather than by the airless void metaphorized by McLuhan in the image of the space between the Apollo spacecraft and the earth.

The title of Tomic’s work signals this work of friction, of difference and deferral, and of negotiation in the service of an aspirational discourse whose constancy cannot be assumed in advance. The title is a fragment of a poem by the Serbian surrealist writer and revolutionary socialist Oskar Davico. Davico developed his prose style during and after the Second World War, as an articulation of the revolutionary movement in Belgrade. The fragment itself is a promise to the future—one day—a commitment to action, to enlightenment through a call to arms, in only the most desperate of times, when light “cannot come otherwise.” Tomic’s performance and video work, however, are not simply committed to the deferral of revolutionary action to an imagined future. She cites sources specifically because of their engagement with the history of political struggle in Belgrade, and with the multiple-scale shift by which revolutionary action is spatialized in the city, the nation, and the globe. The work is also dedicated to the members of the Anarcho-Syndicalist Initiative, and contains the specific notation: Belgrade, 3 September 2009.

In doing this, Tomic joins a return to the sites of historical struggle to the complex multiplicity of social movements in the contemporary moment—the Greek riots in December 2008, sparked by the police shooting of a fifteen-year-old student; the so-called Belgrade 6 activists, accused of inciting, assisting in, and executing an attack on the Greek embassy in Belgrade in 2009 in solidarity with Greek protestors; and by extension movements for social and economic justice through acts of solidarity around the world.

Whereas the landscape unfolding in the video visualizes the spatial dynamics of the revolutionary events of anti-fascist struggle in World War II, the voice-over interviews with partisans provide a temporal narrative of revolutionary change and political praxis. If the lateral movement of Tomic across the sites of anti-fascist resistance is represented synchronically, horizontally, and spatially as ground, the soundtrack and Tomic’s movement itself represent the diachronic, narrative event, the figuration of an historical figure.

The spatialization of the events of resistance can be viewed in relation to the “spatial turn” under postmodernism: the displacement of time, the spatialization of the temporal, registered by a sense of nostalgia in its apolitical form. The possibility of unification, of revolutionary consciousness voiced by the partisans who participated in both the anti-fascist resistance and the emerging Communist movement, would then be read as an expression of nostalgia for nostalgia, a mourning of memory itself, particularly for the possibility of an engaged and political art practice. I believe, however, that Tomic wants to argue against a simple nostalgia, a regressive postmodernism; instead, she asserts the necessity of reinventing a utopian vision in contemporary politics. For Fredric Jameson, the 1960s initiated a renewal of utopian imagination coupled with “the sharp pang of the death of the modern,” but instead of coalescing into a political movement such as socialism, this coupling produced a vital range of micropolitical movements that were “properly spatial Utopias in which the transformation of social relations and political institutions are projected onto the vision of place and landscape” (160). Jameson concludes that spatialization also provides the possibility for thinking the libidinal investment of the utopian and, at the very least, the proto-political.

Tomic’s return to the 1940s is not nostalgic for the revolutionary praxis of the period. She uses several devices to foreground the specificity of the historical moment of anti-fascism, devices that draw out the metaphorical resonances of the weapons of revolutionary struggle. One interviewer stresses the need to develop strategies of resistance suited to the incursions of power themselves:

The fascist power, weapons, technology, tanks … We were no match for them! We had no arsenals nor weapons factories, no supplies. … People gathered to fight. Bare handed? Yes! Our weapons factories were German weapons factories, we took it from them, and beat them with their own weapons.

In the second instance, Tomic herself stages her trespass through the contemporary streets of Belgrade carrying an AK-47 assault rifle, first developed in the Soviet Republic by Mikhail Kalashnikov in the last year of World War II. In the video, the rifle is not raised a single time. Passersby ignore Tomic’s weapon, and she carries it with the same nonchalance with which she carries a plastic bag in her other hand. Yet the weapon is historically specific and thus raises a question—the question—of political action in the contemporary moment. What weapon might serve the purposes of liberatory struggles now? How might the grounds of political action be figured, through what aesthetic and technological mediations?

Tomic’s frenzied crossing of Belgrade in One Day materializes the frictions between the unifying work of “universal aspiration” and the discrepancies of disjunctive social processes in the global system. She does this by staging the friction of the spatial and temporal, of figure and ground, in the cinematic space of media itself. Rather than figuring nostalgia for revolution through a loss of meaning, the video’s refusal of cohesive action, and specifically its refusal to render cinematic space according to the conventions of narrative space, more strongly figures the commitment to a utopian universal aspiration.

Narrative cinema relies on the suspension of disbelief that grants the spectator an omnipotence of vision and mastery over space. Tomic’s continuous and repetitive cutting up of space, on the other hand, refuses narrative coherence at the same time that it enacts a repetitive and circulatory motion in order to articulate the processes of rationalization and reification under capitalism. The formal quality of Tomic’s work thus visualizes—and allows us to grasp—decentered global networks and their differential work in the global system. Tomic says about the work that her “character remains imprisoned in the editing loop of the actual video, unable to find a way out, for this newly-created/old territory.” The aesthetic strategies of One Day are bound to the specificity of contemporary Belgrade, and to the historical aesthetic and material aspects of socially engaged art practice in post-Soviet republics. The commitments of the piece enact a de-virtualization of social relations and of the mediations of technology. In so doing, works such as hers highlight the real material relations that subtend the fantasy of the global village, and also the productive reanimation of other aesthetic forms in the interest of rupturing the machines of our times.

The spatialization and temporalization of One Day reflect the process by which art practice becomes mediated, comes to consciousness as media within a system, and takes on the status of the medium in question. Rather than a heap of fragments (endless posts of amateur video, posters and pictures discarded in the street), protest media may constitute a Gesamtkunstwerk, a synthesis of discontinuous shots, fragments, and historical events through—in this case—the synthesizing force of “creative geography.” The political specificity of Tomic’s work is contained in the spatial and temporal specificity of the referent. Not the production of a utopian space, but rather, in Jameson’s terms again, “the production of the concept of such space” (165). In doing so, Tomic asks about the possibility of representing universal aspirations, about the complexity of positing the unity of social struggle in the deferred and teleopoietic work of time-based media.

Tomic’s piece is therefore not a representation of the interconnectedness between social contexts made possible by new communications technology, not a celebration of protest in the global village, but a question posed in and through media art about the role of scale-making itself for representation and for understanding global and local imaginaries. Her performative act does not act in the service of counter-posing the local against the abstract force of globalization; it is a conjuring of the specificity of universal aspirations in actions, icons, and aesthetic forms. Tomic thus evokes the history of anti-fascist resistance in and for contemporary (globalized) movements.

One Day theorizes space through the fragmented but continuous movement of crossing back and forth across the spaces of revolutionary struggle. Tomic’s movement organizes this “creative geography,” even as her figure is meant principally to dissolve into ground, to stage the sites and conditions of revolutionary struggle. Jameson argues:

[W]hat surely becomes a fundamental property of the stream of signs in our video context [is that] they change places; that no single sign ever retains priority as a topic of the operation; that the situation in which one sign functions as the interpretant of another is more than provisional, it is subject to change without notice; and in the ceaselessly rotating momentum with which we have to do here, our two signs occupy each other’s positions in a bewildering and well-nigh permanent exchange. (87)

The frictions of originary event and secondary one, of figure and ground, of temporal and spatial explanatory frameworks also reverse the causality of political action, in keeping with the shock quality of the conditions of life in the globalized present, marked by financial crises but also by resistance to autocratic rule, corruption, and austerity around the world. These frictions put into question the direction of cinematic migration, such that the origin of the cinematic event is undone from within, in the echoes between two terms that don’t resolve into primary and secondary, figure and ground, cause and effect.

In this regard, W.J.T. Mitchell argues that the icons of the global revolution of 2011 specifically were “not of face but of space; not figures, but the negative space or ground against which a figure appears” (“Image” 9). For Mitchell, the anti-iconic images served to protect protesters against police repression, but also (through Guy Fawkes masks in New York) to figure anonymity as the face of the assembled masses. Instead of icons of revolutionary agency, the revolutionary movements have figured occupation itself as the icon of revolt. The strategy of occupation frequently involves the taking up of space to stage the refusal to make present a set of definite demands. (Mitchell cites as examples silent vigils by Buddhist groups, the wearing of gags or tape over the mouth, and the technology of the “mic check.”) He argues, “The aim, in other words, is not to seize power but to manifest the latent power of refusal and to create the foundational space of the political as such, what Hannah Arendt calls ‘the space of appearance’ that is created when people assemble to speak and act together as equals” (“Image” 10).

Similarly, the footage included in One Day focuses on a referent—the precise location of historical events—but Tomic’s action presents instead the “abstraction of an empty stage, a place of the Event, a bounded space in which something may happen and before which one waits in formal expectation” (Jameson 92). As nothing actually happens in the footage, the place becomes “degraded back into space,” the “reified space of the modern city, quantified and measurable, in which land and earth are parceled out in so many commodities and lots for sale” (Jameson 92). This is foregrounded in Tomic’s crossing back and forth in front of a shopping mall, formerly the site of the first act of sabotage on the part of the People’s Liberation Movement: setting fire to a cistern in the yard of the “Ford” garage on Grobljanska Street.

In the voice-over narratives, by contrast, we have a series of (un-visualized) events, the events of resistance, of successful attacks. Beyond the mediating framework of testimony and visual display, the referent itself is disclosed: the fact of resistance across the frames of reference, not encapsulated by them, with no originary event. The problem of reference is located in and through the medium, in its synthesizing work, stripped of the utopian aspirations of the former period. The structural logic of the tape is in its process of production, rather than in its content. The images of bridges, train tracks, and bus stations foreground the colliding forms of globalizing processes, and thus also of media strategies, which visualize the frictional force of time-based media rather than its resonating interval.

Fig. 1. Milica Tomic, One day, instead of one night, a burst of machine gun fire will flash, if light cannot come otherwise (2009). Photo by Srdjan Veljovic. Used by permission. Courtesy of the artist.

Tomic has reflected on her use of Kuleshov’s editing technique:

This territory, even though it is made up of emancipatory politics, decisions and actions, is imprisoned and occupied by a new time, the era of permanent war. Therefore, a new politics is not to be found yet, and that is why my character, even though she knows precisely where she is going, still wanders and roams, remaining imprisoned within a framework given long ago. But this character, even though she waits and wanders, knows what she is looking for on the basis of previous experience: a new universalistic politics, outside organizations, movements and groups, solitary, singular but international. (“One Day”)

Tomic locates the public intervention and video work in the context of “permanent war” and discourses of terrorism in the twenty-first century. Today, resistance is recoded as terrorism, and languages of security and anti-terrorism justify state acts of violence. For Tomic, the resistance of the Partisan movement would be read today as terrorism, even though their actions were anti-fascist and revolutionary, acts of “war against war.”

This recoding is foregrounded by Tomic’s frenzied return time and time again to the railway bridge on Kardordeva Street, no longer crossing it to and fro, backwards and forwards, in the time of historical memory, but approaching it from above and below, crisscrossing the site in a frenetic questioning pattern. The bridge—now covered in graffiti, an out-of-the-way space—is actually the site of a prevented action. Miladin Zaric, a teacher from Belgrade who lived in the vicinity, noticed that German soldiers were transporting packages of explosives to the bridge. Zaric had been an army officer and had participated in the liberation wars in 1912. Using a spade to cut the conductors that would detonate the explosives, he prevented the Germans from blowing up the bridge in 1944 as they were retreating.

Tomic’s piece provides an allegory for the work of universal aspiration in the anachronistic, defamiliarized language of creative geography. The term occupy similarly functioned to name a universal aspiration, to “mark space,” in the language of creative geography. This follows Mitchell’s argument regarding the rhetorical force of the poster “Occupy Everything,” which marks “occupy” as a “transitive verb” that can take objects from specific places and historical conjunctures (Wall Street, Tahrir Square) and expand or contract them to or from the entire world (“Image” 12). In such global pictures, there is the consciousness that media doesn’t fill a void, that friction exists between the incommensurable scales of “occupation,” in the moments and spaces in which protest is articulated.

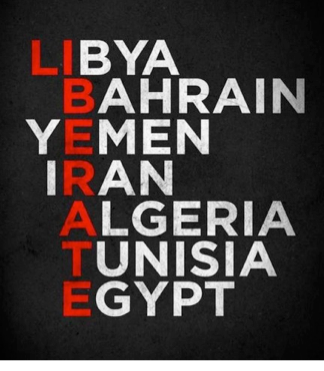

The frictions of media technologies and languages in the contemporary moment highlight both the multiplicity and unity of representational counter-regimes that are articulated in local idioms, respond to (and are entangled with) the official channels of dominant visual culture, and summoned out of the actions of resistance and the icons of state violence. Such counter-regimes are also unified by representational translations that mirror conditions elsewhere. Mitchell, for instance, notes that the establishment of medical facilities, food services, libraries, clothing dispensaries, and communication centers in Zuccotti Park and Tahrir Square constituted “a positive mirroring of that other form of the encampment that has become so ubiquitous on the world stage, the shanty towns and improvised refugee camps that spring up wherever a population finds itself displaced, homeless, or thrust into a state of emergency” (“Image” 14). Aesthetic strategies gesture towards the universal aspiration of a global or regional uprising, as, for instance, the poster in which the names of the countries Libya, Bahrain, Yemen, Iran, Algeria, Tunisia, and Egypt are aligned vertically so that their selected letters spell out “LIBERATE” (see Fig. 2), or the semiotic slippage cited above between the printemps arabe and the printemps érable in Montréal.

Fig. 2. Poster circulated during the Arab Spring.

In each of these cases, the formal and aesthetic strategies are central to figuring the potential of protest media (infrastructures, icons, and idioms) as forms rather than simply platforms. Media in their reflexive forms articulate social and economic conjunctures, examining how specific representational processes have material, social, and semiotic effects, interpellating different audiences and viewing positions, drawing from idiomatic and accented semiotic codes, and referring to social realities that require complex mediating frameworks. Activist art thus has the potential to theorize the possibilities of new media in producing a complex and emancipatory unity, under the sway of globalization but not sheltered behind the walls of the global village.

Footnotes

[1] This essay was written more than a year before the widespread protest that followed the failure to indict Officer Darren Wilson in the shooting of Mike Brown, the failure to indict Officer Daniel Pantaleo in the chokehold death of Eric Garner, and the shooting death of Tamir Rice. Its analysis is closely bound to the global dimensions of the social movements that erupted in 2011 and 2012 and does not (and cannot) address the complexity of the moving demonstrations that emerged in November and December of 2014 in response to systematic police violence against black bodies in the US and elsewhere.

[2] One such protest in Houston, in this case at a meeting of the world’s top energy executives, involved activists dressed in pig costumes to represent the greed of the 1% (Ordonez).

[3] The relations between art activism and protest movements have been twofold: On the one hand, the language of occupation has been mobilized for activism in the art world. For instance, an activist art group sought to “occupy” an artwork by Japanese artist Tadashi Kawamata and architect Christophe Scheidegger entitled “Favela Café” at the 2013 Art Basel fair (“Police”). On the other hand, activist artists have produced art interventions in support of protest movements or issues. An example of this form of activist art includes the Occupy L.A. “Chalk Walk,” an art action planned to coincide with a monthly gallery night (“Art Walk”). In this action, protestors took to the streets with colored chalk, and transformed the downtown landscape into a gallery of artworks and political messages written on walls and sidewalks (Trimarco).

[4] While McLuhan’s understanding of media was especially attuned to the developments of broadcast television in the 1950s and ’60s, the development of the Internet in the 1990s rekindled McLuhan’s media theory for describing the possibilities of the World Wide Web for materializing the “global village.” The financial failures of the twenty-first century (the dot-com bust followed by the housing crisis) have made appeals to the “global village” doubly out of step with the times (with the promises of both modernity and postmodernity). It is interesting that the very critiques of the speculative capitalism that produced the financial crises of the last decade are seen (by champions of social media) to represent the promise of the “global village.” For a historicization of McLuhan’s optimism, and the ensuing cynicism of Baudrillard in the 1980s, see Huyssen 6-17.

[5] While McLuhan’s notion of a “resonating interval” might describe the space between the different instantiations of “Occupy” around the world, we might also be tempted to consider the space between social movements not as a resonating but rather as what Trinh T. Minh-ha calls a “reflexive” interval, “where a positioning within constantly incurs the risk of de-positioning, and where the work, never freed from historical and socio-political contexts nor entirely subjected to them, can only be itself by constantly risking being no-thing” (48).

[6] Government online forums such as the Syrian Electronic Army have passed off staged footage as on the ground accounts and, conversely, accused amateur producers of doctoring images in Photoshop to produce false visual proof of police brutality. See Dickinson 133.

Works Cited

- Bellafante, Ginia. “Gunning for Wall Street, With Faulty Aim.” New York Times. The New York Times Company, 23 September 2011. Web. 14 August 2013.

- Dickinson, Kay. “In Focus: Middle Eastern Media.” Cinema Journal. 52.1 (Fall 2012). Print.

- Do Not Kill Registry. N.p., n.d. Web. 3 October 2013. http://www.donotkill.net.

- Fernandes, Sujatha. “The Mixtape of the Revolution.” The New York Times. The New York Times Company, 29 January 2012. Web. 3 October 2013.

- Grossberg , Lawrence. Cultural Studies in the Future Tense. Durham: Duke UP, 2010.

- Groys, Boris. 2008. Art Power. Cambridge: The MIT Press, 2008.

- Heath, Stephen. Questions of Cinema. Bloomington: Indiana UP, 1981. Print.

- Huyssen, Andreas. “In the Shadow of McLuhan: Jean Baudrillard’s Theory of Simulation.” Assemblage 10 (December 1989). Print.

- Jenkins, Henry, Sam Ford, and Joshua Green. Spreadable Media: Creating Value and Meaning in a Networked Culture. New York: New York UP, 2013. Print.

- Kilkenny, Allison. “Correcting the Abysmal ‘New York Times’ Coverage of Occupy Wall Street.” The Nation. The Nation, 26 September 2011. Web. 15 August 2013.

- Kuleshov, Lev. Kuleshov on Film: Writings of Lev Kuleshov. Ed and trans. Ronald Levaco. Berkeley: U of California P, 1974. Print.

- Lynes, Krista Geneviève. “A Discrepant Conjuncture: Feminist Theorizing Across Media Cultures.” Ada: Journal of Gender, New Media, and Technology. Issue 1.15 November 2012. Web. 14 Aug. 2013.

- McLuhan, Marshall. Understanding Media: The Extensions of Man. New York: McGraw Hill, 1964. Print.

- McLuhan, Marshall and Bruce R. Powers. The Global Village: Transformations in World Life and Media in the 21st Century. New York: Oxford UP, 1989. Print.

- Mitchell, W.J.T. “Image, Space, Revolution: The Arts of Occupation.” Critical Inquiry. 39.1 (Autumn 2012): 8-32. Web. 12 Dec. 2015.

- —. “Preface to Occupy: Three Inquiries in Disobedience.” Critical Inquiry 39:1 (Autumn 2012): 1-7. Web. 12 Dec. 2015.

- Mulvey, Laura. “Visual Pleasure and Narrative Cinema.” Feminism and Film. E. Ann Kaplan (Editor). Oxford: Oxford UP, 2000.

- Ordonez, Isabel. “Occupy Spirit Spreads from Wall Street to Oil Conference.” The Wall Street Journal. Dow Jones and Company, Inc., 6 March 2012. Web. 14 August 2013.

- Paik, Nam June. Global Groove. Video. 1973.

- Penny, Laurie. “Cyberactivism from Egypt to Occupy Wall Street.” The Nation. The Nation, 11 October 2011. Web. 14 August 2013.

- “Police v.s. ‘Favela Café’ Occupation at Art Basel (Switzerland).” ArtLeaks. ArtLeaks, 17 June 2013. Web. 14 August 2013.

- Tomic, Milica. “One day, instead of one night, a burst of machine-gun fire will flash, if light cannot come otherwise.” Milica Tomic. WordPress.com, n.d. Web. 1 Feb. 2013. <https://milicatomic.wordpress.com/works/one-day-instead-of-one-nighta-burst-of-machine-gun-fire-will-flash-if-light-cannot-come-otherwise/>.

- —. One day, instead of one night, a burst of machine gun fire will flash, if light cannot come otherwise (Oskar Davico—fragment of a poem). Video. 2009.

- Trimarco, James. “Occupy Los Angeles Blends Art & Activism.” YES! Magazine. Positive Futures Network, 1 Aug. 2012. Web. 14 Aug. 2013.

- Trinh, T. Minh-ha. When the Moon Waxes Red: Representation, Gender and Cultural Politics. New York: Routledge, 1991. Print.

- Tsing, Anna. Friction: An Ethnography of Global Connection. Princeton: Princeton UP, 2005. Print.

- “We Are All Khaled Said.” Facebook, 10 June 2010. Web. 3 Oct. 2013. https://www.facebook.com/ElShaheeed.